LIVING TOGETHER, LEARNING APART

Can separate

be equal?

Scroll down to read more

Can separate be equal?

Two schools shift emphasis from

desegregation to education equality

The two elementary schools, Jean Parker and Charles Drew, are among the most segregated schools in San Francisco. Parker, in Chinatown, is 82 percent Asian. Drew, in the Bayview, is nearly 70 percent black.

Parker is a high-performing school. Drew is not.

Such racially lopsided schools would have been targeted under forced desegregation based on the U.S. Supreme Court’s statement 60 years ago that separate is never equal. But, for the most part, those efforts have been relegated to the history books.

Yet Drew and Parker are at the center of local, state and federal efforts to address segregation, not by desegregating or diversifying the schools, but by making them as equal as possible compared with one another and with whiter and wealthier schools when it comes to high-quality staff, facilities, computers, materials, and extras like art, music and after-school programs.

Prudence Carter, Stanford

University Graduate School

of Education professor

The effort shifts the emphasis from shipping kids across town so they can attend schools with more diversity to building high-quality schools in every neighborhood.

In California, the state’s new education funding system seeks to tip the scales toward that equality, giving districts that educate primarily low-income students or English learners — disproportionately children of color — up to $3,600 more per student.

In San Francisco, district officials give the 22 highest-needs schools — primarily those with the highest number of African American students, English learners and poor students — extra staff, funding and support on top of the extra state funding. Drew is among those receiving the extra support since 2010.

The state’s and city’s efforts are relatively recent, which means it’s hard to tell yet if more money and staff will make a difference. The hope is that if all schools are good schools — equal schools — perhaps diversity will follow.

“People are going to go where they know their children are going to receive a quality education,” school board member Shamann Walton said.

At Jean Parker

Parker is already considered a quality school, at least based on standardized test scores. Although 90 percent of its students are from low-income families and nearly two-thirds are considered English learners, the school scored above district and state averages on the most recent tests.

Those results aren’t surprising.

“Racial isolation works for white students. Racial isolation works for Asian students,” Prudence Carter, a professor at the Stanford University Graduate School of Education, said during an April school board meeting on school assignment. “Racial isolation doesn’t work for African American and Latino students.”

Cultural differences, historical disadvantages, as well as family education and income levels are among the contributing factors to that discrepancy, experts say. Asians are more likely to delay childbearing, live in two-parent households and have household members with at least a high school diploma, according to the Annie E. Casey Foundation, which researches child well-being.

Annie E. Casey Foundation 2014

report “Race for Results”

Still, the district receives extra federal and state funding for Parker’s disproportionate number of low-income students and English learners. The additional funding allows the elementary school to have a full-time social worker and other extra staff and resources to help students struggling with problems at home or in school.

“Test scores don’t always show social functioning, whether a student is comfortable raising their hand, or sharing an opinion,” said the social worker, Melissa Oliva-Sullivan.

While she doesn’t want to play in to stereotypes related to race, Oliva-Sullivan said she considers culture to help students struggling socially or behaviorally. While many of the students excel academically, they might struggle socially, unsure how or when to ask another student to play with them or how to participate in class.

So, twice a week, one day for boys and one for girls, she offers an alternative to the outside lunch recess — indoor game time featuring origami, board games and other activities that fifth-grade students can do together in an informal social setting.

On a recent Thursday, a dozen boys showed up, a handful gathering around Oliva-Sullivan to play Apples to Apples, an interactive, word association game. The boys laughed as they selected nouns from cards in their hands, say “volcano” or “sea slug,” to go with an adjective that may or may not relate, like “miserable.”

The boys giggled about one another’s silly selections as Oliva-Sullivan kept one eye on the game and the other on any student who might want to play.

“They’re really academically focused,” she said. “They need a little more practice with their social skills.”

At Charles Drew

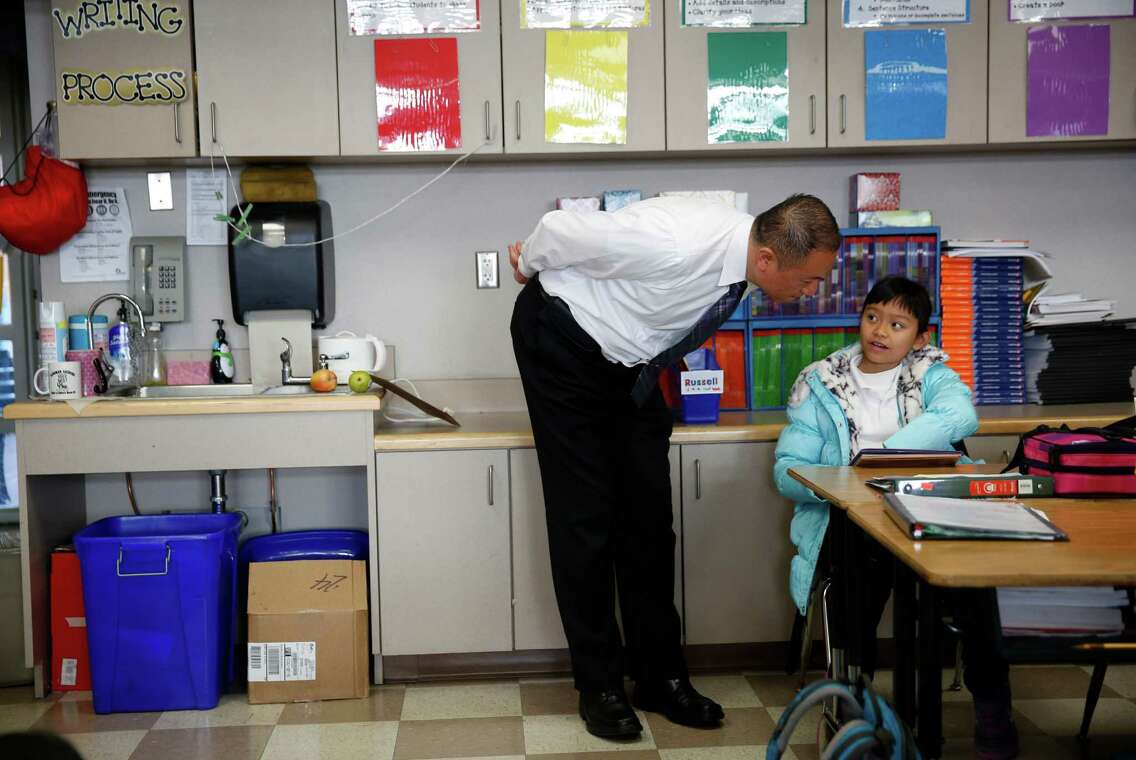

At Drew, Principal Tamitrice Rice-Mitchell doesn’t mince words when she talks to prospective families about her school. It’s mostly African American.

“It’s the first thing I say to parents,” she said. There are 243 students overall, including 166 African American, 31 Latino, two Asian and one white. Nearly all, more than 93 percent, are poor and 17 are English learners.

The school is among the lowest performers on standardized tests, with most students living in low-income neighborhoods with disproportionate violence.

With the extra funding, Drew has a behavioral coach, literacy coaches, a school climate consultant to address safety and the overall environment at the school, after-school programs, security staff, a social worker, recess activity coordinators, and a parent liaison.

It’s all about taking care of each child and his or her needs, said Rice-Mitchell, who believes that’s what a quality school does.

“Too often, children of color grow up in environments where they experience high levels of poverty and violence,” according to the 2014 Casey Foundation report, “Race for Results.” “Such circumstances derail healthy development and lead to significant psychological and physiological trauma.”

All that has long been reflected in Drew’s test scores.

Yet Rice-Mitchell believes the Bayview school is a good school, one with dedicated teachers and extra resources to help address the significant needs of the students who attend.

“Why do you have to go across town for a quality education,” she said. “Say that we’re all integrated. Does that create that somehow?”

Lakeshore Elementary is among the city's

most diverse student bodies

most diverse student bodies

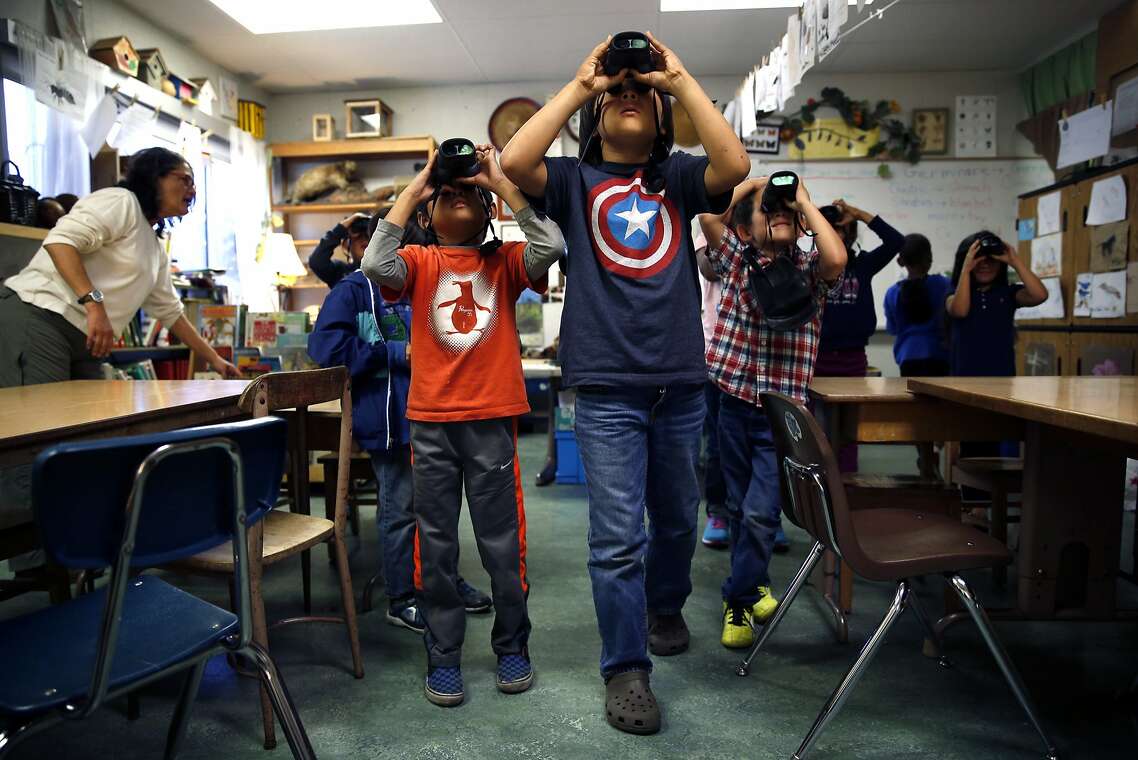

Nineteen kindergartners wriggled as their teacher draped a handmade dragon costume over their heads. The eyes on its glittery cardboard head glowered.

“The dragon parade will be starting in just a few minutes,” the teacher, Athena Lafferty, announced over the school’s loudspeaker one February morning at San Francisco’s Lakeshore Elementary. “How do you say ‘Happy New Year’ in Chinese?”

“Gung hay fat choy,” the children obliged.

Lakeshore Elementary, a lively school not far from Lake Merced, is among the San Francisco public elementary schools that best represent the school district’s racial makeup. Last year, 36 percent of Lakeshore students were Asian, 17 percent were Latino, 15 percent were black and 13 percent were white. The same year, the district’s population was 36 percent Asian, 27 percent Latino, 10 percent black and 13 percent white.

The Chinese New Year Parade is one of many activities Lafferty and her colleagues at Lakeshore use to teach their students about the different cultures that make up the fabric of their school — and their city. In one corner of the classroom sat a box of books by African American authors, to help them learn about Black History Month. The school’s weekly newsletter is published in both English and Chinese.

Citywide draw

Race is only one way Lakeshore is diverse, said its principal, Matthew Hartford. With students from all over the city and from different socioeconomic backgrounds, “It’s not just code for ‘we have people from a lot of race groups,’” he said. Last year, 55 percent of Lakeshore’s students qualified for free or reduced-price meals.

“On the tour, when I have prospective parents come, I speak to our diversity right away: Don’t come here if you don’t want to grapple with a diverse school,” he said. Families from different backgrounds have different cultures, customs and communication styles. Some Lakeshore students enter kindergarten having gone to preschool, while others have to catch up.

Matthew Hartford, Lakeshore

Elementary School principal

“On the tour, when I have prospective parents come, I speak to our diversity right away: Don’t come here if you don’t want to grapple with a diverse school,” he said. Families from different backgrounds have different cultures, customs and communication styles. Some Lakeshore students enter kindergarten having gone to preschool, while others have to catch up.

For the most part, San Francisco schools with higher poverty levels and larger proportions of minority students scored lower on the Academic Performance Index, a measure that’s fallen out of use with the state of California, but that parents still use as an indicator of school quality.

Lakeshore was no exception, scoring 771 out of 1,000 on that measure — below the 830 district average for elementary schools. But Hartford, who has taught overseas and worked at several schools across SFUSD, said the lessons students learn at diverse schools are invaluable.

“A child coming through our school will be able to relate to just about anybody,” he said.

Integration falters

Scholars agree that diverse schools better prepare students to live in an increasingly multicultural society, but districts across the United States have lost the momentum to achieve them. In San Francisco, a district that has all but given up on integrating schools, no magic formula makes Lakeshore more diverse than most other elementary schools.

One reason is its legacy of drawing students from all over the city, Hartford said. In the 1980s, Lakeshore was one of the district’s alternative schools, intended to attract students citywide. Such schools were once so coveted for their special programs and high test scores that parents camped out for nights at a time to secure a kindergarten spot.

Though it has a neighborhood attendance area, Lakeshore still pulls many of its students from across the city. To accommodate crosstown travel, three buses travel to Lakeshore each morning, one each from the Outer Mission, the Bayview and Visitacion Valley — more buses than most of the district’s elementary schools receive.

Busing, now voluntary in San Francisco, is not as common as it once was. In 2012, the number of general education buses was reduced from 30 to 25 for the 2013-14 school year, down from 44 buses in 2010-11, largely because of budget cuts.

Under today’s school assignment regime, Lakeshore is far from the district’s most popular school. Last year, only 12 of 54 kindergartners who lived in its attendance area ranked Lakeshore as a school choice at all.

Meeting family's needs

Though Cleveland and Monroe elementary schools are closer to her family’s home in Mission Terrace, Joanna Hasse is happy to have her daughter, Lizzie, at Lakeshore. She watched as the 6-year-old and her classmates paraded through hallways under the dragon costume.

But it wasn’t a first choice when Hasse and her husband listed schools.

“I just listed kind of the top schools, the ones that I had seen that I’d liked, and then all the schools where I knew people who were happy,” she said. She hadn’t visited Lakeshore, but a friend recommended she put it on her list. She didn’t know that Lakeshore was one of San Francisco’s more diverse schools when she and her husband visited.

Matthew Hartford, Lakeshore

Elementary School principal

“We come from an interracial family. My husband is Lithuanian and I’m Caribbean and white, and so for us to find a school that represents our family is difficult,” she said. “We needed a school where there were not only lots of different types of people, but also families that are interracially mixed.”

Parent Loretta Chien said the school prepares her daughter, Naia, to live in a diverse city like San Francisco.

“She came home singing Hanukkah songs that we don’t know about, and then she came home talking about Day of the Dead,” she said. When Naia comes home talking about her classmates’ backgrounds, “We have the chance to talk to her about different people, different ethnic groups, so I think it’s great.”

Greta Kaul is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. E-mail: gkaul@sfchronicle.com